|

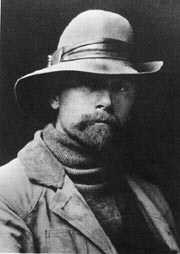

Edward S. Curtis

The Curtis

Studio in Seattle was where society girls went to have their portraits made in the late

1890’s, tradition had it. A portrait by Curtis gave them "glamour." But if

they were drawn also by the aristocratic person of the young proprietor, six feet two,

athletic, and with a well-trimmed Vandyke beard, they were usually disappointed. The Curtis

Studio in Seattle was where society girls went to have their portraits made in the late

1890’s, tradition had it. A portrait by Curtis gave them "glamour." But if

they were drawn also by the aristocratic person of the young proprietor, six feet two,

athletic, and with a well-trimmed Vandyke beard, they were usually disappointed.

More often than not, Edward Sheriff Curtis was away taking pictures of Indians. His

fascination with Indians as subject matter began when he came on Princess

Angeline, aged daughter of Chief Sealth (whose name somehow

came out "Seattle" when it was given to the city), digging clams near the shack

where she lived on Puget Sound. "I paid the princess a dollar for each picture I

made," Curtis recalled a long time afterward. "This seemed to please her

greatly, and she indicated that she preferred to spend her time having pictures taken to

digging clams."

Indian subjects appealed to him further after he visited the Tulalip reservation one

morning, hired the Indian policeman and his wife for the day, and made many photographs.

He went back another day and made some more. He gained the confidence of the Indians, he

explained, by saying "We, not you. In other words, I worked with them and not at

them."

After taking pictures of the Indians for three seasons, he entered three—The

Clam Digger (the background for this Web page), his very first; Homeward; and

The Mussel Gatherer—in the National Photographic Exhibition and won the

grand prize. Sent on a tour of the world, the prize-winning pictures took prizes wherever

they went, including a solid gold medal.

Curtis achieved these results with a massive 14 x 17 view camera, using glass plates.

He had bought the camera from a prospector heading for the California gold fields who

needed a grubstake.

Not that there weren’t more sophisticated cameras to be had. Modern photography

had been heralded a good many years before, in 1880, when George Eastman introduced the

dry plate, bringing exposure time down to a fraction of a second.

Edison’s invention of the electric light also had given a boost to photography by

dispensing with the need for a skylight. Now the studio could be brought down to the

ground floor, precluding the need to ride an elevator or climb the stairs.

Photography became so popular in the 1880s that artists, among them John Singer

Sargent and James McNeill Whistler, put aside brush and palette to experiment with the

camera as a means of self-expression—as David Octavius Hill, the well-known Scottish

portrait artist, had done long before with a far more primitive camera, using it for three

years before returning to his easel.

Then came Eastman’s Kodak, the first handy, hand-held camera With a fixed focus,

it took circular pictures 2 ½ inches in diameter and carried a roll of 100 exposures.

Photography became a craze rivaled only by that of the bicycle. "There was a fan in

every family," observed Scientific American in 1896. For those who

couldn’t afford to buy a camera, manuals were published showing them how to make

theft own, much as in the natal days of radio, in the early 1920s, many built a

"wireless" themselves.

- from Visions of a Vanishing Race by Florence Curtis Graybill (E. S.

Curtis's daughter) and Victor Boesen

|